In the 1980s, cigarettes were sold in colorful, elegant packages without health warnings. They were symbols of status and desire. Decades later, when governments began to include images and risk messages, it was already too late: tobacco had become the world's leading preventable cause of death.

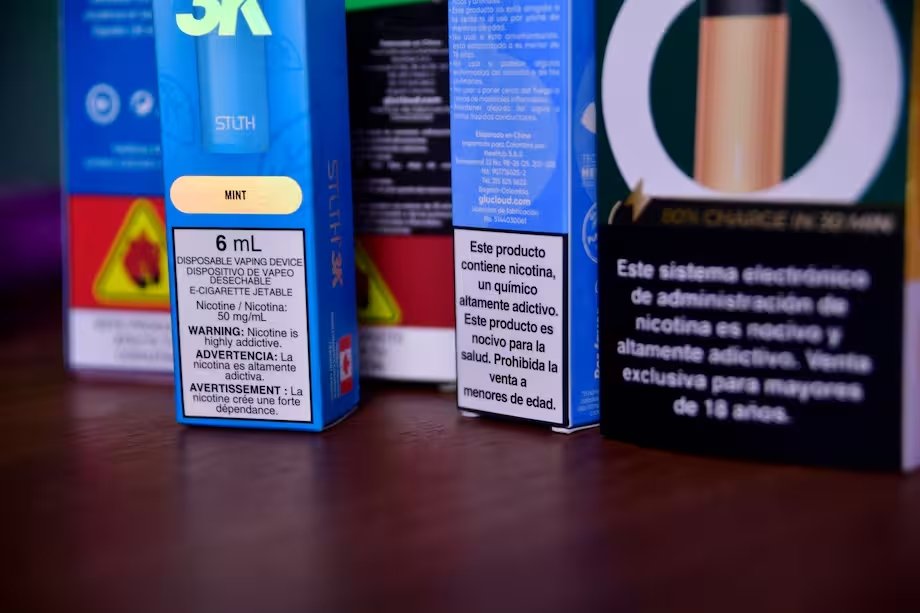

Today, history could repeat itself with vapes. Their packaging, full of colors and flavors that evoke fruits or desserts, seems harmless and attracts teenagers. But behind the eye-catching design, there is a void: weak or non-existent warnings about the harms of nicotine, a highly addictive and noxious substance. In Peru and Colombia, the messages are small, confusing, and lack a clear standard. What should alert to a risk ends up hiding it.

An analysis by Salud con lupa, in collaboration with El Espectador of Colombia, reveals that the packaging of five vape brands lacks uniform criteria and, in many cases, does not comply with current regulations. The packaging of Vuse, Veev, Geek Bar, STLTH, and GluCloud—the latter of Colombian origin and not available in Peru—was reviewed, acquired between June 20 and July 1, 2025, in Lima and Bogotá. The devices were purchased in stores strategically located near universities and institutes, spaces frequented by young people and minors.

The problem is not just the variability in packaging, but the wide room to maneuver that companies have to shape the narrative of their products. In many cases, warnings are reduced to a generic phrase about nicotine addiction or a simple mention that the product is "only for those over 18." This flexibility allows them to evade clear communication of risks and replace it with ambiguous messages, which soften the harms or hide them under attractive language. Thus, buyers do not have a precise idea of what they are really consuming.

The governments of Peru and Colombia have already passed laws—one stricter than the other—but the industry continues to find ways to evade them, as this analysis shows. In Peru, the law grants companies up to two years to adapt, but that period only begins to run when the regulations are published. The Ministry of Health formed a technical team on May 5, with the goal of having the regulations ready by September 3; but the deadline passed, and the document has still not been presented. As long as it remains pending, the sector maintains wide room to maneuver, and the process can drag on indefinitely.

In Colombia, on the other hand, none of the four brands analyzed comply with the current provisions, even though the adaptation period has already expired.

The warning messages on the packages should also be clear and visible, but this is not the case in any of the analyzed instances. Companies also fail to provide complete or legible information about the ingredients, relegating details to instructions placed inside the packaging—such as use restrictions or the type of medical attention needed in case of harm to health. This information is not accessible at a glance and, in brands like Geek Bar, is not even available.

Only precise regulation and constant supervision can ensure that consumers know the real risks of these products and that public health is effectively protected.

Peru: Packaging with Reduced Warnings

In Peru, the vape industry communicates the risks of its products unevenly and with unclear messages. The law, in effect since November 2024, establishes that these products must include on their packaging the phrase "Sale to minors under 18 prohibited," in addition to informing consumers about the presence of nicotine and the effects of its consumption. However, the regulation that must define how to comply with these obligations has not yet been published.

This lack of precise criteria has left a gap in labeling that companies have filled in their own way: each brand decides the tone, location, and size of the warnings. This can lead consumers to underestimate the risks, especially given the widespread idea that vapes are less harmful than cigarettes.

The communication strategies of the four brands analyzed vary widely. Vuse, from the tobacco company British American Tobacco, and Geek Bar, from the Chinese company Guangdong Qisitech Co., Ltd., use a simple and generic message: "This product contains nicotine. It is an addictive substance." In the case of Geek Bar, the warning even appears in English, without adaptation for the local public.

Veev, from Philip Morris International, includes a similar message, although slightly more explicit: "This product is not risk-free and contains nicotine, which is addictive." STLTH, of Canadian origin, opts for a more forceful tone: "Nicotine is highly addictive and harmful to health," without specifying what type of harm it can cause.

This diversity in labeling prevents consumers from truly understanding the risks. Furthermore, the packaging omits other effects associated with vaping, documented by independent studies, such as respiratory problems or cardiac deficiencies, limiting themselves to mentioning nicotine and its addictive nature.

Another critical element is the size of the warnings. None of the six products analyzed—three from Vuse, two from Veev, one from STLTH, and one from Geek Bar—reaches the 30% occupancy on both sides of the packaging, as required by law. In general, they are between 15% and 25%, concentrated mainly on the front. Geek Bar places warnings on both sides, but they only occupy 25%. STLTH is the only one that reaches 30%, although only on the front, which also constitutes non-compliance.

The manufacturers' adaptation criteria—so varied among themselves—reduce the overall impact of the warnings and make it difficult for consumers to quickly identify safety information. Furthermore, this disparity can become a problem if there is no effective supervision by the competent authorities.

That responsibility will fall to the National Institute for the Defense of Competition and the Protection of Intellectual Property (Indecopi), as confirmed to Salud con lupa. The entity responded in writing that its Inspection Directorate will develop "in due course" a strategy to supervise both packaging and advertising in convenience stores and other points of sale. This process has not yet been fully defined due to the delay in the approval of the law's regulations, the drafting of which is in the hands of ten entities, including the Ministry of Health.

Information about ingredients is also limited. The analyzed products only include some basic components, such as propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, nicotine, artificial flavors, benzoic acid, lactic acid, and water. However, scientific research shows that vape aerosols can contain hundreds or even thousands of additional substances—including heavy metals and volatile organic compounds—that are not mentioned on the packaging. This lack of transparency raises serious questions about the information available to consumers and their ability to make informed decisions.

Another important point is the nicotine concentration declared by the tobacco companies. In a preliminary investigation we published in January 2024, we found that Vuse Go vapes—which at the time had no major competitors in the country—declared 20 mg/ml of nicotine, possibly because the products were designed according to UK regulations, where British American Tobacco is headquartered. At that time, Peru did not yet have a specific rule for this market. According to merchants from the Peruvian Association of Vapers (ASOVAPE), many consumers preferred Chinese vapes, which offered higher nicotine levels than Vuse.

A year later, the picture has changed: Vuse now declares 34 mg/ml of nicotine, an increase that reflects competition with brands offering even higher concentrations. Veev, from Philip Morris, declares 38 mg/ml; Geek Bar and STLTH, 50 mg/ml. Unlike the United Kingdom, Canada, and several European Union countries—such as Spain, Germany, or Italy—Peruvian regulations do not establish a maximum limit for nicotine concentration, allowing each company to set its own levels, despite it being a highly addictive substance.

Colombia: Vape Manufacturers Fail to Comply with the Law

Unlike the Peruvian case—where the law's application depends on the approval of still-pending regulations—in Colombia, the law regulating electronic cigarettes is already fully in effect. The rule, in force since May of this year, equates vapes with conventional cigarettes and establishes the same restrictions on advertising, sale, and labeling. Furthermore, the one-year period granted to companies to adapt their packaging to the required standards has already expired. In theory, no product should be on the market today without meeting these conditions. In practice, however, the opposite occurs.

The main brands available in the country—Vuse, from British American Tobacco; Veev, from Philip Morris International; STLTH; and GluCloud, the first Colombian company dedicated to manufacturing these devices, with a presence also in Spain and the United States—fail to comply with the law's provisions in various ways. The most evident is the lack of uniformity in the warning messages and the proportion they occupy on the packaging.

By equating the packaging of electronic cigarettes with that of tobacco products, Colombian law is particularly strict. It prohibits designs aimed at minors or that are especially attractive to them; bans any insinuation that consumption is associated with athletic, professional, social, or sexual success; and prevents the use of misleading expressions like "suave," "light," "mild," or "low in nicotine." It also requires the message: "This product is not risk-free and contains nicotine, which is addictive" to appear clearly and unequivocally. These warnings must appear on both sides of the packaging and occupy a considerable space.

In the reality of markets and convenience stores, however, the story is different. The Vuse vape—from British American Tobacco—openly violates the rule: in two of its presentations (Vuse Go 1,000 and 5,000 puffs) it does not include the health warning, limiting itself to a minimal age restriction indication on the front.

Veev Now Ultra—from Philip Morris International—does reproduce the official message, but only on the front, which constitutes partial compliance. STLTH, for its part, uses a more emphatic variant: "Nicotine is highly addictive and harmful to health." GluCloud and Veev—in their GluCloud BoxPod and Veev Now presentations, respectively—are the only ones that resort to a more graphic resource: "This product affects your heart," accompanied by an image of a slightly fragmented heart. It is not as stark a warning as those that appear on cigarette packs, but it stands out for its clarity and direct message.

This disparity—ranging from generic phrases to specific warnings about heart health—harms the consumer, who does not receive uniform or consistent risk communication.

There is also no uniformity in the proportion that the warnings occupy on the packaging. Veev vapes, from Philip Morris International, reserve around 25% of the front; STLTH reaches 30%, although only on one side. GluCloud's products are the only ones that comply with Colombian regulations, occupying 30% on both sides of the packaging, at least in one of its models, the GluCloud XL.

As in the Peruvian market, the products analyzed in Colombia mention a very limited number of components—propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, nicotine, flavorings, and nicotine salts—which suggests a deliberate omission of potentially dangerous substances. This lack of transparency is a cause for concern: consumers are inhaling products without knowing their exact chemical composition.

The Colombian Ministry of Health assured El Espectador that, since the rule came into effect, it has deployed several actions: issuing specific health warnings, reviewing 2,156 labeling simulations, and holding training sessions for health secretariats and the public on the risks of consumption. However, market evidence shows that, despite having a robust regulatory framework, business adaptation is advancing slowly, and irregularities remain the rule rather than the exception.

This report was developed as part of a journalistic project led by Salud con lupa, financed by Vital Strategies on behalf of Bloomberg Philanthropies. Its content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the position of the financing entities.